What if we could write loose coupling services without the overhead of common microservices architecture? In 2015 Valim wrote an article entitled Elixir in times of microservices, where he elaborated his idea on how Elixir fits in a microservice architecture. That’s the kind of mind-blowing post that challenges us to experiment different ways to write software, and that post is my practical approach on this matter.

TL;DR

-

Create an umbrella project;

-

One app for each bounded context;

-

An app should never call internal code from another app;

-

Use a module on each app to act as a public API to exchange data between apps, and also to call functions to mutate data;

-

An app should never return its internal data structures on public apis, it should return only raw data like maps and lists;

First of all, what’s a Bounded Context ?

If you know nothing about it, I recommend to read this Martin Fowler article before continuing.

According to the great book Domain Modeling Made Functional:

[…] domains and subdomains in the problem space are mapped to what DDD terminology calls bounded contexts — a kind of subsystem in our implementation. Each bounded context is a mini domain model in its own right. We use the phrase bounded context instead of something like subsystem because it helps us stay focused on what’s important when we design a solution: being aware of the context and being aware of the boundaries. Why context? Because each context represents some specialized knowledge in the solution. Within the context, we share a common language and the design is coherent and unified. But, just as in the real world, information taken out of context can be confusing or unusable. Why bounded? In the real world, domains have fuzzy boundaries, but in the world of software we want to reduce coupling between separate subsystems so that they can evolve independently. We can do this using standard software practices, such as having explicit APIs between subsystems and avoiding dependencies such as shared code.

That give us some hints on how we should implement a bounded context:

-

Should be independent

-

Should have an explict API to exchange data

-

Avoid shared code

Umbrella Projects

If you know the concept of umbrella projects, you may be thinking that we can implement each bounded context as applications of an umbrella project. And you’re right, but some rules are required in order to keep clean organization and avoid creating a mess that is hard to evolve.

But what’s an umbrella project and apps ?

An app is just a package of code, it could be a tiny library, a component, a subsystem or a full application. An ERP system can be composed of apps like Customer, Billing, Delivery and so on.

And an umbrella project is a project composed of those apps, which lives in the same project and can be dependent on each other.

Want to read more about it ? Go to Using an Elixir Umbrella post.

Show me the code

Enough talking, let’s see how it works. And let’s use the same example from Martin Fowler article to establish an example that we can use for our system.

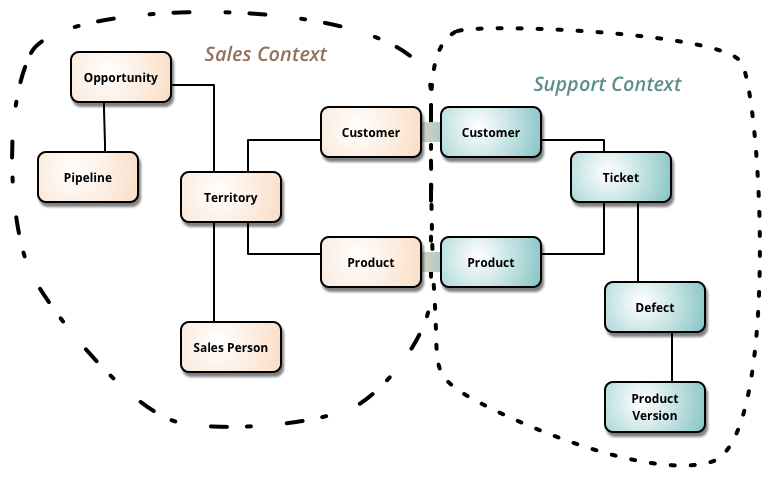

Bounded Context example from Martin Fowler article

In this example we have 2 bounded contexts, Sales and Support, with their own rules and knowledge. Remember that each context should be independent, so let’s start by creating a new Elixir umbrella project called “SystemX” with two apps:

➜ mix new system_x --umbrella

➜ cd system_x/apps

➜ mix new sales

➜ mix new support

You’ll end up with the following directory structure:

➜ tree

.

├── README.md

├── apps

│ ├── sales

│ │ ├── README.md

│ │ ├── config

│ │ │ └── config.exs

│ │ ├── lib

│ │ │ └── sales.ex

│ │ ├── mix.exs

│ │ └── test

│ │ ├── sales_test.exs

│ │ └── test_helper.exs

│ └── support

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── config

│ │ └── config.exs

│ ├── lib

│ │ └── support.ex

│ ├── mix.exs

│ └── test

│ ├── support_test.exs

│ └── test_helper.exs

├── config

│ └── config.exs

└── mix.exs

Entities

As you can see in our domain, we have the entity Customer on both Sales and Support context. That’s because each context may have specific rules or data and evolve independently, which give us leverage to modify each one of them without breaking the whole system, because it’s limited to the inner context.

Let’s define each Customer:

# apps/sales/lib/domain/customer.ex

defmodule Sales.Domain.Customer do

defstruct [:id, :name, :address, :score, :has_support_ticket]

end

# apps/support/lib/domain/customer.ex

defmodule Support.Domain.Customer do

defstruct [:id, :name, :last_ticket_id, :email]

end

Public API

And what happens if the Sales context needs to get some information from the Customer on the Support context ? That’s when the explict API comes in handy. Let’s say we need to know if a Customer has a support ticket, then we need to ask this information for the Support context. So, let’s create the Support explicit API to return a Customer:

# apps/support/lib/support.ex

defmodule Support do

def get_customer(customer_id) when is_integet(customer_id) do

find(customer_id) # get customer from db

|> Map.from_struct()

end

end

Returning a map instead of a struct is what give us loose coupling between apps. We will talk more about it in a moment.

Putting into practice

Now, let’s create a service in the Sales context that calculates the current customer’s score. The business rule is: It gives a higher score if the customer has no ticket support (I know it’s not the best example in the world…)

# apps/sales/lib/client/support.ex

defmodule Sales.Client.Support do

alias Sales.Domain

def get_customer(%Domain.Customer{id: customer_id} = customer) do

customer_has_support_ticket =

customer_id

|> Support.get_customer()

|> has_support_ticket()

%Domain.Customer{customer | has_support_ticket: customer_has_support_ticket}

end

defp has_support_ticket(%{last_ticket_id: last_ticket_id}) when is_nil(last_ticket_id), do: false

defp has_support_ticket(_), do: true

end

# apps/sales/lib/service/customer.ex

defmodule Sales.Service.Customer do

alias Sales.Domain

alias Sales.Client

def current_score(%Domain.Customer{} = customer) do

customer = Client.Support.get_customer(customer)

case customer.has_support_ticket do

false -> 100

true -> 50

end

end

end

Ok, there’s more than just a simple service. Let me explain.

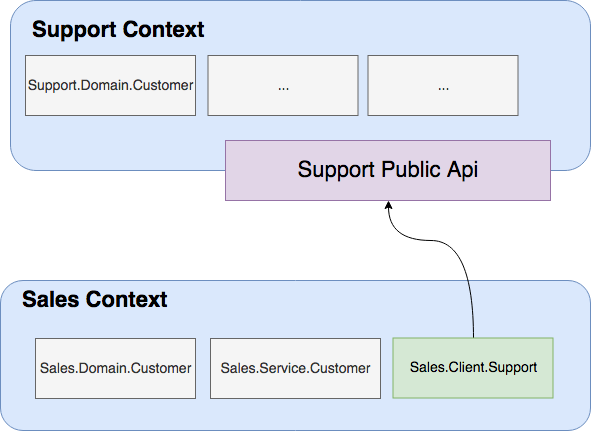

Apps are allowed to comunicate with each other only by a public API. Boxes in gray are for internal use only.

A Customer entity in the Sales context knows nothing about support tickets, as expected because this information is of responsability of the Support context, however we need it to build our service Sales.Service.Customer.

To overcome this lack of information in the Sales context we can ask the Support context for this information, but remember that we can’t share code between apps nor call internal code from another app. That’s the objective of a public API and the reason it can only return raw data like maps and lists instead of returning an internal struct from Support app.

But we don’t want a meaningless map being used internally in Sales app, we actually want that our domain reflect the real life by mapping it to a struct, which is done in Sales.Client.Support — receives a map, use the information it needs and fullfill Sales.Domain.Customer. Note that in Sales.Domain.Customer we don’t keep the attribute last_ticket_id because we don’t care about the actual ticket id in the Sales context, we just need to know if it’s empty or not. Remember that the same entity from the real world may have different attributes according to the context.

Converting the data structure on the boundaries makes the service layer cleaner and easier to write and understand because in layers below the public API we deal with validated data structures prepared for the current context, which means you don’t need to worry with dirty data, which frees us from writing conditional code.

Maintenance

And there’s one more reason to do this kind of data convertion on the boundary: maintenance.

What would happen if you used the struct Support.Domain.Customer all over your Sales context in services, domain, tests and so on… and for some reason you had to rename the attribute last_ticket_id to any other name ? Yeah, that’s right… you’d have to change a lot of code. But using a client allows you to handle this scenario in the client while keeping the struct Sales.Domain.Customer exactly the same, avoiding a major refactor. Just the client layers changes. It’s a simple example but I think it’s enough to get the ideia.

How to organize the internal context code is not in the scope of this article.

Contract

You may be wondering: if the public API returns a map, how can I know the content (contract) of this map ? Which attribures are present or not, which data type I should expect and so on ? And how can I know if the call was successful ? The answer is: use Typespecs.

defmodule Support do

@type customer :: %{id: integer, last_ticket_id: integer}

@spec get_customer(integer) :: {:ok, customer} | {:error, binary}

def get_customer(customer_id) when is_integet(customer_id) do

# your logic here ...

# return the common pattern {:ok, data} or {:error, data}

{:ok, customer}

end

end

Typespecs is about transparency. You know what to expect from calling the function and also what that function expects as parameter. And it also has the advantage to generate an useful documentation using ex_doc library or even a live documentation by using text editors that supports that.

However it does not enforce an “automatic data validation”, that means you can pass an Integer even if the typespec says that it’s expecting an String. To assist you in the task of obeying the contract, I recommend using Dialyxir that tool will do a static code analysis and warn you if anything is out of expected.

When should I use an umbrella app ?

Putting everything inside just one app or splitting each part into umbrella apps is a question of balance and following some rules. Creating many apps may be overkill, but it’s worth considering creating a new app in some cases:

-

That part of the system is developed by another team, be it an internal or offshore team in the same company or an outsourced team.

-

That part of the system is shared between more than one app. That’s a more common scenario for shared libs.

-

That part of the system needs to be deployed separately in another server or in a different permission schema (some are public and some are private). — Distillery releases can help you with that.

-

Need to use more than one framework in the same system.

Everything else can live in the same app perfectly.

A note about umbrella projects

An umbrella project may get out of control if you don’t follow some rules like we discussed here. Think in each app as being isolated, ie: you can remove it from umbrella without breaking too many things. That’s the reason we can’t call internal functions from another app and need to rely on a public API.

There’s nothing in Elixir that forbids or prevents you from calling internal code from another app, instead of only using the public API. That’s a convention you’d have to adopt and always review the code to not break this rule.

Another commom issue with umbrella projects is circular dependencies that happens when app A depends on app B and for some reason you also try to make B depends on A. Then you get a circular dependency error. You have to carefully design the relationship between your bounded contexts to avoid this situation.

Another observation it that not everybody likes working with umbrella projects, and that’s fine. The same ideia and rules applies if you work with separated apps.

Summing up, umbrella project sits between monolithic and microservices. And if done right, you gain the best of both worlds.

Bonus: distributed apps

Umbrella project is a good way to start a new project and get things running, but it has known issues that may cause problems in the future. But don’t worry too much about it because the approach discussed here can evolve to break apart those apps into distributed apps by implementing each public API as a GenServer, which can be global registered using tools like Swarm or Horde. But that’s subject to another post, let me know if you want to hear more about it.

What I didn’t say

Domain Types, Anti-Corruption Layers, CQRS, DTOs, Sagas, CRDT and some other techniques and patterns can be useful in this kind of architecture, but I can’t talk about everything in just one article and you may not need all of it. Keep in mind the first and most important step is to organize your project to enable it to evolve in a agile way.

Thanks Eduardo Hernandes for the hours discussing Elixir, DDD and some crazy stuff and also for reviewing this article.